Decolonizing Education through Diplomacy

Alternative Text: A group of children holding flags smiling in front of a globe.

Alternative Text: A group of children holding flags smiling in front of a globe.

By Amlata Persaud, Ed.D., Childhood Education International

"Decolonizing has to be a collaborative journey and a collective struggle of committed individuals. It is one of undoing and redoing, of unlearning to relearn, of questioning, reconsidering, and being open to different possibilities." -Farhana Sultana (Human Geography, 2009)

Decolonization can be understood as the identification, rejection, and dismantling of influences and practices that reflect or perpetuate colonial power paradigms.

As practitioners within global education organizations, it is important that we engage with this concept, as well as recognize that the term itself is contested and potentially problematic. Ironically, the origin of the word has been described as Eurocentric, and some critiques have centered around the misappropriation of decolonization as a “buzzword” that masks continued attempts by the global minority in the Global North to dominate the international development paradigm.

As we engage with the work of decolonizing education and reflect during Global Action Week for Education, we should be prompted to critically question the very idea and implications of “global” education and to interrogate why the system, our organizations, and we ourselves function in the ways we do:

What is the goal of global education? What are the motivations of global education organizations? How are they organized and to whom are they accountable? Whose knowledge influences their understanding and operation? Which voices are valued and included? Which epistemologies and methodologies are valued, and why? How are programs and approaches developed, designed, and delivered?

Through these types of questions, we can begin to confront the long shadow of colonialist thought and behavior that continues to influence how we work in explicit and implicit ways. We can examine the non-inclusive language that we use, question the (lack of) diversity in development practice, interrogate power imbalances in global partnerships, and scrutinize the skewed nature of knowledge production in international and comparative education.

We must also consider our positionality – many of us who seek to engage in decolonial approaches to education and international development are embedded within the very agencies, organizations, and systems in need of transformation.

The stickiness of this situation has long been recognized by post-colonial thinkers, from Frantz Fanon, who asked us to consider how we extricate ourselves, to Nina Asher (2009) who posed the enduring question: How then do we break out of recreating, recirculating, and transmitting colonizing educational structures and practices when we ourselves are enmeshed in the same? (pp. 72-73)

There are no easy answers to this question, and it can be a deeply uncomfortable inquiry. Unterhalter and Kadiwal (2022) describe adopting decolonization as praxis in teaching and research as being “profoundly personally destabilizing.” They point to the need to turn the mirror onto ourselves and reflect on our “positionality, privileges, and complicity in relationships of injustice.” (p.11)

In recent research, Menashy and Zakharia (2022) demonstrate the perpetuation of colonial racial power hierarchies in global education governance and call for “global education actors to consider their own part in embodying and reproducing this ignorance.” (p. 480)

It is difficult but imperative that we resist complicity and constantly wrestle with the neo-colonialist contradictions we may face in our work.

As we do this, we need approaches that can ground us and provide actionable steps to reject the perpetuation of colonialist practices. There are examples of bold efforts to dismantle colonialist approaches, which often require visionary and courageous leadership and buy-in from all involved and should be applauded. There are also smaller shifts we can make in our ways of thinking and working that can have incremental but wide and enduring impacts on the system as a whole.

In developing models that can guide us as education practitioners in our efforts to advocate for and utilize decolonial approaches, concepts from the field of Education Diplomacy can potentially be leveraged.

Education Diplomacy is a field of practice in the global education sector that incorporates the skills of diplomacy to build partnerships and solve complex education challenges using collective action. As conceived by Childhood Education International, Education Diplomacy can be used to advance education through reform and transformation and by helping people, organizations, and governments seek agreement and take collective, collaborative action on critical education issues.

For some, a diplomatic approach might seem like the very antithesis of decolonization, since decolonization has historically been conceived of as a necessarily disruptive and even violent – rather than diplomatic -- phenomenon. Here, however, Education Diplomacy suggests that amid heterogenous decolonial approaches, diplomacy skills could enable us to effectively explore and challenge decolonial practices together, particularly in the way that education is delivered.

Because power imbalance still exists, partnerships and collective action – hallmarks of the current global education landscape – are potential minefields for perpetuating colonialist practices and behaviors. Yet, they also offer a real opportunity to approach decolonization collectively as global education practitioners and to make deeper, long-lasting and far-reaching change. In the opening quotation to this piece, Sultana (2019) reminds us that decolonizing development is a “collective struggle” that requires a shared vision and journey moving us beyond the existing power dynamics that have been inherent in colonial systems.

In thinking about how we can use Education Diplomacy as a methodology to advance decolonization in the education sector, the work of scholars Alasuutari and Andreotti (2015) is inspiring. They use “HEADS UP” as a pedagogical tool when developing decolonizing dispositions in North-South partnerships. Each letter of the exhortation for practitioners to keep their “HEADS UP” when engaging in global partnerships represents an important point to beware of: “Hegemony, Ethnocentrism, Ahistoricism, Depoliticization, Salvationism, Un-complicated Solutions, Paternalism.”

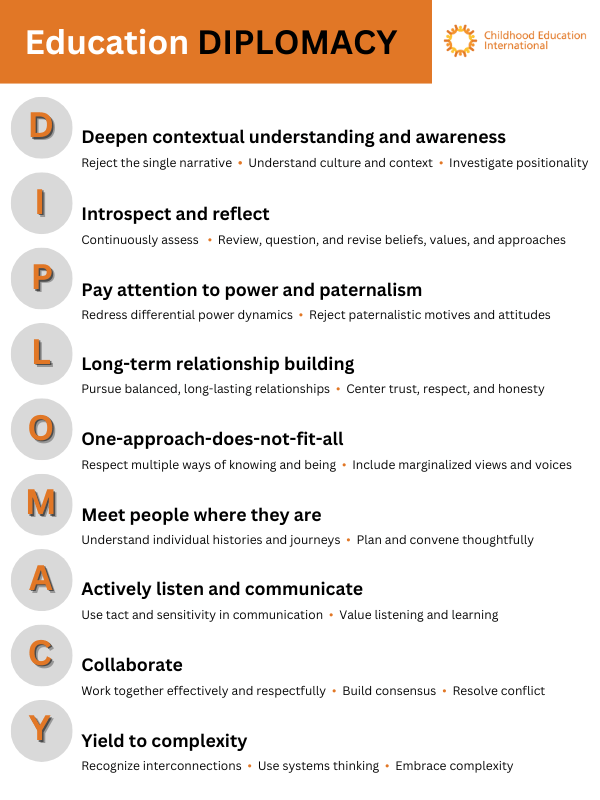

A mnemonic can also highlight how key insights and practices from Education Diplomacy can be used to advance decolonizing work in education. As we collaborate with others and within our organizations to design, develop, and deliver education programming, we can promote decolonial approaches when we exercise “DIPLOMACY”:

In the spirit of embarking on this collective journey to decolonize our mindsets, approaches, and practices as global education practitioners, I invite you to share your thoughts and reactions to this exploration of Education Diplomacy.

If enough of us embrace meaningful decolonizing ideals and can tangibly and intentionally apply them, then perhaps together we can begin the work of unraveling and breaking free of the systems in which we are enmeshed.

Sources referenced:

Alasuutari, H., & Andreotti, V. (2015). Framing and Contesting the Dominant Global Imaginary of North-South Relations: Identifying and Challenging Socio-Cultural Hierarchies. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, (20).

Asher, N. (2009). Chapter 5: Decolonization and education: Locating pedagogy and self at the interstices in global times. Counterpoints, 369, 67-77.

Menashy, F., & Zakharia, Z. (2022). White Ignorance in Global Education. Harvard Educational Review, 92(4), 461-485.

Unterhalter, E., & Kadiwal, L. (2022). Education, Decolonisation and International Development at the Institute of Education (London): A Historical Analysis. London Review of Education, 20(1), 18.

Sultana, F. (2019). Decolonizing development education and the pursuit of social justice. Human Geography, 12(3), 31-46.

Dr. Amlata Persaud is the Global Practice Area Lead for Leadership at Childhood Education International. She is committed to work that supports equitable and inclusive provision of high-quality education for all persons around the world. Amlata has worked in education research, training, project management, and policy analysis roles in multiple countries around the world. She has an Ed.D. in International Education Development from Teachers College at Columbia University and an MPhil in Development Studies from the University of Oxford.